For months, the square in front of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art has been home to families of Gaza hostages. Artist Roni Taharlev, whose one-woman show in the Museum, Not this Light, the Other Light, is closing soon, after being extended twice, says that the sadness, the desperation, and the pain of the families seep through the museum’s walls and into the exhibition.

“It is impossible, and I do not wish to ignore it,” she says. “The Museum opened again; the square had already become ‘Hostages Square.’ I go through the square every time I come here, I visit the families sitting in their tents, and somehow it seems that the proximity changes the art.

“For instance,” she continues, “as part of the exhibition, there is a group of small portraits of young girls sleeping. When we were working on the exhibition, the curator, Galit Landau-Epstein, insisted on including these works. I was not convinced. They seemed too sweet to me – not relevant to the exhibition. But Galit insisted, saying that we don’t have other drawings and pastel works, so eventually, I agreed. Returning to the museum after the reopening, the same works suddenly took on a completely different meaning. Suddenly, they were not so sweet anymore. They became the most chilling and most relevant to what had happened to the girls in our thoughts. And once they took on that meaning, I cannot look at them differently anymore. It seems that art, too, changes with the circumstances.”

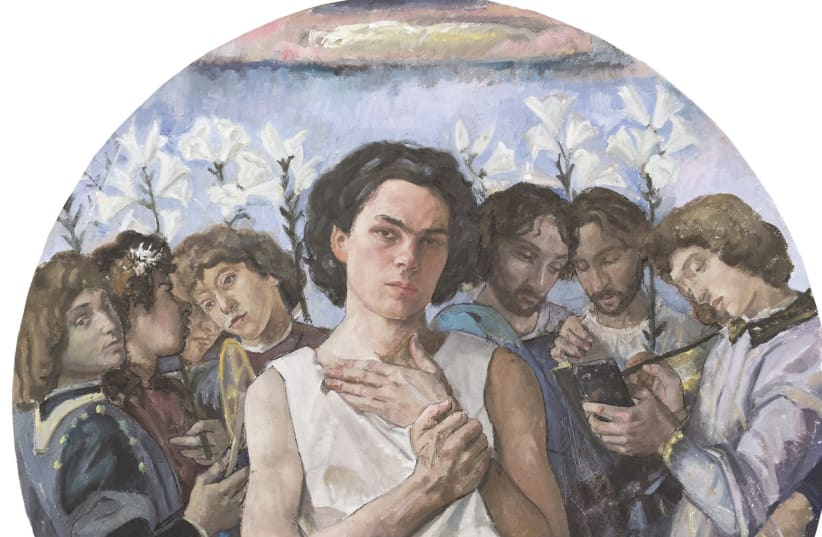

The recipient of the 2022 Haim Shiff Prize for Figurative-Realist Art, Taharlev maintains a longstanding, intimate dialogue with the human body, resonating with art history and often quoting works by the masters while delving into neglected themes of body and gender and engaging with contemporary social issues.

Her exhibition was the most successful this year at the museum, drawing thousands of visitors, many of whom returned again and again.

“It has been amazing,” says Taharlev. “I never expected so many people to be interested.”

During an event hosted at the museum last week, Mira Lapidot, the museum’s chief curator, remarked that when it comes to Taharlev, they’ve come to anticipate the unexpected. “We extended the exhibition twice, due to public demand. The guided tours Roni and Galit, the curator, held were always overbooked and filled as soon as we advertised them, and even tonight, in an event that usually attracts family, friends, and colleagues, there is not an empty seat in the auditorium.”

The exhibition also features several significant bodies of work created by Taharlev over time. These include self-portraits alongside a powerful portrait of her mother and a series of charcoal and pastel drawings that are being displayed for the first time.

“Even when I’m traveling by train and there’s a breathtaking view, I am more fascinated by the person sitting across from me,” she says. “First, I have an image in my head. That is where my work begins. Then I understand it. The painting begins with the image, not the narrative. My focus is on the body. Willem de Kooning claimed that ‘flesh was the reason why oil painting was invented.’ I feel the same way.”

But her narrative is inescapable: “In this exhibition, the figures are of women who don’t conform to the ideal body, and that brings about technical questions such as, How do you draw cellulite? There aren’t many references to such subjects in art history because artists haven’t focused much on the maturing female body. How do you draw veins in the legs? There’s no theory you can read. You squint your eyes, and the more you work, the more things open up. The more I work with these materials, the more layers unfold, and more questions arise.”

“I chose to focus on older women sitting in unfamiliar poses,” says Taharlev. “We are used to seeing women posing in uncomfortable poses that are essentially the product of the male gaze. I try to break out of this very narrow framework. I realized there are poses we don’t deal with and facial expressions we don’t explore. I am drawn to that. I draw what I see. In this exhibition I could see how this point of view was [for the audience] like sprinkling water on dry land, how there was a thirst for it because it is not present in many works. Some women visiting the exhibition reacted to the works, saying, ‘This is mine. I’m here in these paintings. I look at myself in the mirror every day, and here, at the exhibition, I find myself; I see me.’ This is important because women, especially at these ages, are often transparent. They are erased. They supposedly don’t exist.”

Combining the contemporary and the historical

TAHARLEV’S PAINTINGS convey ties to painting from Titian through Euan Uglow, Paula Rego, and many others. But these ties, which she calls “a well of inspiration,” stay in the background when you see the works in the exhibition. The works are not illustrations to a narrative but, rather, a study of the human body – of femininity, age, and beauty. As the artist explains, they really are not about anything specific. “I usually paint the female body, although I have a few paintings of men, especially in works when I dealt with gender issues,” the artist admits, adding that it is also a matter of what’s available. “There are more female models, and it’s more available and straightforward,” she confesses.

A contemporary artist, Taharlev chooses figurative paintings, a technique that seems less related to modern art. But the vibrancy, the subjects, and the presence of the body as it is, devoid of the male gaze, is in fact very contemporary. “Anything human is not foreign to me. I’m willing to go through the entire spectrum of emotions, of ages, to delve deep,” she says.

The technical narrative connects to it. The subjects change with the passing years as the technique evolves. “Even in the works of Titian or Rembrandt, you see that the older the artist, sometimes the figures also grow old. There’s something in the proximity of the end, so to speak, that allows you to see the person through the body and delve inward. If content and technique are not integrated, it doesn’t work. Over the years, the subject also changes; the light is different, a different palette. It’s all tied to technique.”

As for artists who inspire her, Taharlev says she would need an hour and a half just to recall all of them. “It can change,” she says. “First of all, there’s Lucian Freud. And there’s Paula Rego and Balthus, with whom the relationship is, I would say, complex. But there were years when I was more influenced by him; now, maybe a bit less.”

“Euan Uglow, an excellent British painter, is an inspiration, and Victor Man. I’m constantly influenced by many painters, and if you’re looking through art history, then it’s endless. Titian and Caravaggio and, of course, Velázquez, the Roman painting, can’t be forgotten. It really takes hours to mention them all.”

“Over the years, I sometimes wanted to be Titian, Botticelli, or Rembrandt. Now, all of them are already within me. Their art is a part of free aspiration. Like a well which is there and I can draw from it, drink from it, a little bit every time. The inspiration is already within me, and the process is intuitive,” she says, trying to explain her process. “The main desire is to paint human form, to paint the body.”

Roni Taharlev’s exhibition, Not this Light, the Other Light, is showing at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Curator Galit Landau Epstein. The exhibition closes on May 25.